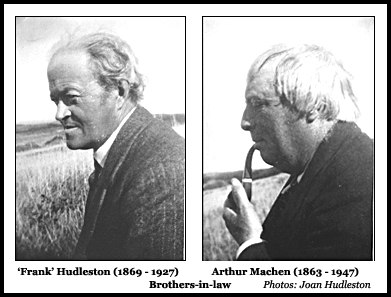

Note: Arthur Machen was married to Joan's aunt Purefoy Machen (nee Hudleston).

The following article in Mother's scrap-book is probably taken from the English "Listener" magazine - March 29 1956.

(Reproduced with the kind permission of Anthony Lejeune).

An Old Man and a Boy

Memories of Arthur Machen by ANTHONY LEJEUNE

WHEN we look at the difficult business of growing up, most of us, I Imagine,

can pick out one or two people whose influence on our young lives was far greater

than we understood at the time. There was something about them, orsome casual remark

they made, that took root in our minds and grew. I remember with particular gratitude

one very old gentleman, with a mane of white hair touching the collar of his ancient

Inverness cape. He was half blind, half deaf - but wholly alive.

I was about fifteen then, and I was just beginning to make all sorts of exciting

new discoveries in the world of books. I liked what the Americans call 'off-beat'

stories - strange stories - and I had recently come across some very strange

stories indeed. They were not ghost stories in any ordinary sense, but they

were all thee more frightening because they dealt with horrors that were never quite

described. They hinted at dark things, at half-remembered rituals and evil

powers which might still he lingering among the foxgloves and hawthorn around some

mossy stone. They were finely and flawlessly written, and their author's name was Arthur Machen.

During the summer holidays, I happened to have lunch with John Betjeman who was

an old friend of my parents. I asked him if he had ever heard of this man Machen.

Yes, he said, he knew him well. Machen was now almost eighty and lived in complete

retirement at Amersham. Why did I not go and see him? The old gentleman would be

delighted.

A few weeks later I walked down from the railway station through the woods

to the wide village street of Old Amersham.

A few weeks later I walked down from the railway station through the woods

to the wide village street of Old Amersham.

Machen lived in a small flat on the first floor of a rather ugly red-brick house.

He answered the bell himself, looking dishevelled and surprised to see me. I am sure

he had made little of Betjeman's letter and had no idea who I was. But he received me

with great courtesy, gave me tea, and talked to me as one gentleman to another,

both men of the world, equal in age and understanding.

After that 1 used to go and see him every two or three months. Usually we would lunch

together at an old coaching inn; and, as a rule, my parents and Machen's wife came too.

Machen used to sit by the fire, puffing away at an evil-smelling pipe and sipping gin

and pale ale. It was always gin and pale ale in those days, though 1 have heard

that long ago in his wild youth he preferred absinthe at the Cafe Royal. 'What's the time,

Arthur?' my father asked him once. 'Time for a drink' he answered, in his beautiful deep voice.

Return to Top

Splendid Company

Mrs Machen was a small wrinkled woman, some years younger than her husband. Her

name was Purefoy. Once upon a time she had been a chorus lady and she had a fund

of anecdotes about eccentric theatrical landladies. Nowadays her whole life was devoted to looking after Arthur. One day, while Machen was holding forth in the grand manner, I remember hearing her whisper to my mother: 'just think, I've had all these years of that splendid company'.

Arthur Machen was splendid company. He took conversation seriously as an art.

When he raised his hand and announced, 'Literary anecdote', everyone within

earshot stopped to listen. The local chatter about tractors and turnips

died away and he held he whole room spellbound. He talked often about the giants

of literature, particularly his favourites - Dickens, Rabelais, and Cervantes.

'When I was a young man' he said,'I used to read Pickwick Papers, Don Quixote,

and Rabelais once each year. Now I read Pickwick once a year, Don Quixote only

once every two years, and Rabelais every three years - but 1 think that is the

inverse order of their true importance'.

About his own work he had less to say. He was never really satisfied with it.

Always, he felt, he had been on the verge of a masterpiece, but - the

vision half-perceived vanished when he stretched out his hand to take it. His

quality had been recognised by the award of a small civil-list pension on which

he lived; but by the standards of popular success he was a failure. His stories

had - and, indeed, still have - a small and secret following. But his books of

criticism and autobiography, into which he put his best work were not the stuff

to make either best-sellers or a highbrow fashion. They belonged to a time

in the eighteen-nineties when Machen lived in seedy London lodgings, dining on

crusty bread and green tea, earning a meagre living by making a catalogue of books

on occultism, and trying to escape from his loneliness into dreams of the Welsh

hills where he was born.

Some years later, he became a journalist on a national newspaper, and a most unusual

journalist he must have been. He once overheard his news editor discussing which reporter

should be sent out on an assignment. 'If we send Smith', said the harassed editor,

' we shall get a story. If we send Machen we may get a very good story'.

No, doubt it was Smith who went.

His one real commercial success came to him by accident and he was rather

ashamed of it. In September 1914 he wrote a short story called 'The Bowmen'.

It was about a section of British soldiers in France, hard?pressed by a German

attack. One of them, a scholarly fellow, calls upon St. George for help,

and they are saved by a ghostly company of English archers from Agincourt.

It was not even a very good story, but its effect was remarkable. The story was

talked about, quoted in sermons, and reprinted as a pamphlet. That was a time

of rumours and credulity. No sooner had the story of Russians with snow on their

boots been abandoned than the story of a supernatural army took its place. Soldiers

wrote from France claiming to have taken part in the battle and to have seen

it all themselves. The idea of archers gave way to the simpler one of angels.

Machen's story was forgotten and the legend of the Angels of Mons passed into history.

Machen himself was greatly surprised. He tried in vain he to check the

extraordinary rumour he had started, but only succeeded in acquiring some

notoriety and even a little money. In the long run, it did him more harm

than good. He was labelled and remembered as the man who invented the

Angels of Mons, the author of a sharp journalistic trick, not to be trusted by respectable editors.

Soon after our first meeting, I had to write a prize essay on the subject

of tradition. I asked his advice, and he wrote me a long letter in his firm

angular script. Tradition, he said, is a wonderful subject: and he went

on to give examples from his own experience. One told of a mound in Scotland,

which simple people said was the grave of a knight in shining armour. Nobody

believed them, until one morning the mound was found to have been opened by

thieves. All that was left was some bones and two or three of the silver laminae

from the armour. Another told of a certain church with a blank wall before

which the local peasants always bowed. The vicar was curious and scraped at

the surface of the wall. He found a picture of the Virgin which had been

covered over at the Reformation.

Machen's scholarship was wide rather than deep - except in a few curious places.

He loved to roll church Latin around his tongue. 'I can't part with my beloved

Latin tags' he said, 'as dark with antiquity and as well-worn as old farmhouse furniture'.

He hardly ever repeated a story, and he told a great many. He had never been

able to accept wireless or cards as a substitute for talk. 'Cards,' he boomed,

'are a confession of inability to maintain conversation ' His own conversation

would linger sometimes round Caerleon-on-Usk, and the countryside where he spent

his childhood. He loved its deep lanes and dark woods and its memories running back

to Roman times. He told me of one village where each cottage once had a candle in

its window at night. The candles were put there to keep the Little People away.

Sometimes - less often - he talked about London, which he saw as a place full

of mystery lurking beneath drab facades. He lived for most of his working lift in

Verulam Buildings, just off the Gray's Inn Road. Saturday night was always his

'at home' day, and scores of famous people had been his guests. The only one

he seemed in the least proud of having known was Amundsen, the explorer. He

liked to recall how Amundsen stood warming himself at the hearth one winter

night and said 'You know, Arthur, nobody who hasn't been up to his

waist in the freezing slush of the Arctic can properly enjoy a fire like this'.

Return to Top

On the Stage

But what Machen liked best to talk about was the year or so he spent on tour

with Frank Benson's company. He was already a well-known writer, and no one

could understand why he suddenly decided to go on the stage. He seemed to have

wandered into the theatre by accident. A fellow member of Benson's company

describes Machen's first appearance as one of the rioters in 'Coriolanus'.

'We were all brandishing clubs and shouting ourselves hoarse' - 'Down

with him!' 'Traitor!' and there at the back stood Machen, muttering

softly in mild disapproval of Coriolanus, 'Down with him. Traitor.

Oh yes, distinctly traitor, oh impossible fellow'. Before long,

however, he was shouting with the best'.

Machen's theatrical repertoire was not confined to Shakespeare.

His favourite play, which he loved to describe, was a melodrama about a sailor

who had rescued a gorilla from a wicked barber. For years the sailor tried

to teach the grateful gorilla to raise three fingers, but he could only raise two.

But at last the beast saved the hero's life, and, dying in a white spotlight,

he raised - oh, poignant moment! - three fingers. 'Good old Boko', sobbed the

sailor, and clasped him In his arms as the curtain fell. This was one of Machen's

star turns. At the age of eighty-three he was still tremendous in it.

I do not for a moment suppose Machen was a good actor. He was probably a glorious

'ham'. But his time on the stage was the happiest part of his life. He described

it as 'the best holiday a man ever had', and a portrait of Benson hung in the place

of honour over his mantIepiece. He paid tribute to the theatre in every movement he

made, walking through the streets of Amersham, holding court in the bar parlour

with the sweep and size of an old-fashioned actor-manager treading the boards.

This quality of largeness is what stays with me most. It was a largeness

of mind as well as gesture. He was an old man, sunk in poverty and obscurity,

but he talked as though the world were his oyster. He had known more than his

share of failure and loneliness and the destruction of things lie loved,

but he could have said of himself, as he said of Dickens, that ' he believed in God

and all goodness; that is, that the end was well'. To have been friends with

a man like Machen is the best sort of education.

I was away in the Navy when he died. I remember hearing it announced

on the radio in the mess. I thought of him as I had seen him last, walking away

arm-in-arm with his wife down the quiet High Street, in his old Inverness cape

and quaint black hat, with the white hair lying like a halo on his collar. I thought,

too, of a story he used to tell about Benson. An old actor had died, and at the

company's next annual dinner Benson stood up, raised his glass, and said in

a great voice: 'This year one amongst us has answered the call-boy of the stars'.

Return to Top

Footnote: Arthur's Birthday - 1943

AUTHORS BIRTHDAY

To the Editor of The Daily Telegraph

Sir - March 3, 1943, will be the 80th birthday of one of the most distinguished living men of letters, Mr. Arthur Machen. His friends and admirers wish to honour the occasion by a birthday cheque, which will be of practical help to him.

Subscriptions should be sent to Colin Summerford, c.o. Westminster Bank, 1, Stratford-place W.1., cheques being payable to the "Arthur Machen Fund."

Yours faithfully

MAX BEERBOHM, COMPTON MACKENZIE,

ALGERNON BLACKWOOD, EDWARD MARSH,

WALTER DE LA MARE, JOHN MASEFIELD,

A.E.W. MASON, T.S. ELIOT,

DESMOND MacCARTHY, MICHAEL SADLER,

G. BERNARD SHAW.

London.

Return to Top

Mr. Machens Birthday Party

Eighty tiny candles lit up the birthday cake of Mr Arthur Machen yesterday

at a London Restaurant where his friends gathered to do him honour. Sir Max

Beerbohm presided and Lady Benson proposed the toast of many happy returns

and Mr Augustus John seconded it. Mr W.W. Jacobs who will be eighty in September,

and Mr. H. R. Higgett, like Mr. Machen an old Bensonian, and Mr. Algernon Blackwood

were among the veterans present, while many young writers were proud to be there.

Mr. Machen, whose Inverness cloak, Lady Benson declared, was the one she remembered

when he was in the Benson Company, made a speech in his perfect manner that much

affected his hearers. His summing up was that pestilent heretics maintained that

there was no honey in life, also that there were no stings. But he was glad

to say that both statements were utterly false.

The fund for the birthday cheque that will be given to him is open till the end of the month., and Mr Colin Summerford, c/o Westminster Bank, 1. Stratford Place, London, W 1, is the treasurer.

Manchester Guardian 5-3-1943.

|