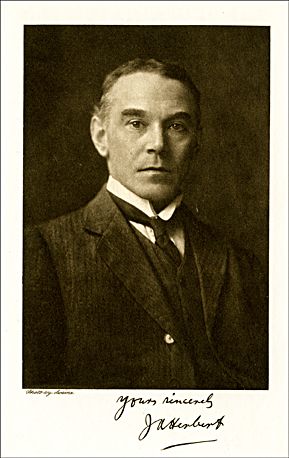

'John Alexander Herbert'

'John Alexander Herbert'

|

|

Deputy Keeper of the Manuscripts in the British Museum. (b.1862 - d. ?)

The illustration above is the only coloured reproduction in a booklet entitled "Miniatures From a French Horae" - British Museum ADD. MS. 16997 Fifteenth Century - reproduced in honour of John Alexander Herbert."

The Museum administration also gave an accompanying letter with the book to 'Sandy' to which he replied. British Museum,24th November, 1927. My Dear Herbert, Your colleagues and a multitude of friends who have known you during the forty years of your service in the Museum wish to give you some token of their regard and esteem at the period of your retirement. Many of us are interested in the same subjects, but all, I think, have experienced your unselfish readiness to give time and thought to help others, whether their special needs came within your own lines of work or involved search outside them. Your work on illuminated manuscripts made it only natural for its, as we hope it will also make it agreeable to you, to think that this token of esteem might fitly take the form of a reproduction from a fine manuscript in the Museum collections, one moreover which we know that you appreciate. The expressions of affection and gratitude which have accompanied the responses of those who have been asked to take part in this little gift we cannot fully convey to you, but we hope you will accept and believe the sincerity with which we all wish you many years of happiness and work when freed from the ties of official position.

Those of us who have the pleasure of knowing Mrs. Herbert have personal reasons for desiring to give her a share in the expression of our very best wishes for you both,

and we all join in asking her to accept a second copy of the book.

38, Gunterstone Road, W. 14. 26th November, 1926. My Dear Gilson, It is quite beyond me to give adequate expression to my feelings on receiving the beautiful book which you gave me this morning, with such kindly and affecting words, on behalf of yourself and our colleagues and a number of kind friends.All I can do is to thank you and them, from the depths of my heart, first and above all for the friendly feelings which the gift betokens, and secondly for the charming, and to me especially gratifying, form in which those feelings are embodied. A more welcome gift could hardly be imagined than so exquisite a reproduction of one of the daintiest and most attractive of our (may I still say "our"?) treasures. I must add, thirdly, the intense pleasure brought me by the gift as evidence that such assistance as I have been fortunate enough to be able to give to fellow-workers, during my forty years in the department of MSS., has been considered useful.

To yourself and my other colleagues I should like to add a word in thankful recognition of the friendly comrade-like spirit which has always characterized our relations. This book will always be a charming reminder to me of those happy years, and of the friends who helped so greatly to make them happy.

38, Gunterstone Road, W. 14. November 26th. Dear Mr. Gilson,

I am puffed up with pride that I am to have a copy of the glorious little book. It is a great surprise - and a delightful one. My warmest thanks for this most kindly "doubling of joys."

II. Some Relatives John Alexander Herbert married Alice Louise Grisewood Baker (b.1867 - d.1942) in August 1896. Alice was Joan Hyde's (nee Hudleston) aunt/godmother. Alice Baker was the daughter of Lieutenant Colonel Richard Aufrere Baker (1830 - 1902) and Louise Milner Birch (1833 - ?1875). Other children were: Grace Emily Baker b.1859; Florence Lydia Baker b.1961 and George Robert Aufrere Baker b.1862. After Louise's death the Colonel had three children by Isabella Anna Maria Fox (1854 - 1888) who was the daughter of Dr. William Fox (1811 - 1875) and Lady Emma Green (?1814 - 1874). The children were: Herbert A. Fox, born about 1877; Leslie Crofton Aufrere Fox (1878 - 1961) and Joan Hudleston's mother, Evelyn Margaret Fox - born about 1883 and died in 1954. There is no reason why Isabella and the Colonel could not have married but on the 3rd May 1988 Isabella Fox married Edward Williams. She died on the 17th 0f December 1888. Her death at the age of 34 was stated to be due to cirrhosis of the Liver and she was said to have been an alcoholic for many years. In turn Joan Hudleston's mother Evelyn Fox also became an alcoholic. Fortunately, alcoholism in my family does not seem to have run any further. I had a reasonably dissipated youth - probably a reaction to an authoritarian childhood and 10 restrictive years in Boarding Schools. At one stage was on a University Drinking Team - the only residual effect seems to be that if I drink alcohol, I run a high risk of a gout attack! Alice Baker had previously married Walter Humbolt Low (b.1864 - d.1894) in 1889 and had three children by him: Ivy Therese (189 - 1977), Letty b.1890 and Olive b.1891. After she married Sandy in 1896 they had one daughter - Rose Herbert.III. Ivy Litvinov's view of her stepfather (Sandy) The only source of information I have on Sandy is from Samuel Lipman's article "Ivy Litvinov, The Commissar's wife" from his book "Music and More"; Ivy Litvonov's short story "She knew she was right" in the book of the same name and John Carswell's book "The Exile: A life of Ivy Litvinov". In what follows I shall refer to the author and page number. Samuel Lipman (p.261) states about Ivy Litvinov (nee Low) that "She had, not surprisingly, an unhappy and confined Victorian childhood, which she nevertheless managed to ride into a youthful literary career as a novelist whose most fully imagined subject was herself." And: "Later she began to be published as a short-story writer, at first in the as always leftist New Statesman, and then after 1966 in The New Yorker. In subject matter, her sentimentally cast stories alternated between memories of a turn-of-the-century childhood and personal accounts of the shabby world of shanty dachas and crude vacation rooming houses available to the superannuated widow of a half-disgraced and totally discarded diplomat. Many of these stories, with all their echoes of other-and better-women writers, were collected and published in 1971 under the title She Knew She Was Right."(Lipman p.265) "She Knew She was Right" details in semi-autobiographical form Ivy's recollections of her mother's courtship by John (Sandy) Hart (portraying her future husband John Alexander (Sandy) Herbert and John Hedley (Mac) depicting Joan Hudleston's father, Frank Hudleston, who later married Alice Herbert's half-sister Evelyn. The aunts Gracie and Florie mentioned obviously represent Alice's unmarried sisters: Grace Emily Baker and Florence Lydia Baker. Wyn or Winifred is her mother Alice Low (nee Baker). Eileen represents the young Ivy Low. The name Winifred could have been borrowed from Frank Hudleston's sister Winifred. In the story she describes Sandy (p.21) "John Hart – Sandy - was only in the British Museum, vaguely associated in the minds of Wyn's sisters and their friends with outsize statues and uniformed attendants. He was small, had a squeaky voice, and told unfunny stories, choking with laughter, to grave faces, compelling attention with the bore's uplifted finger."

It appears that Ivy never fully accepted Sandy as a replacement for her father Walter Low who died at the age of 30 when she was 5 years old.

"Although Sandy was a progressive man, it was painful to him that his wife insisted on having what she called her 'personal life'. This, at the time thev were married, consisted mainly in reviewing novels for the Queen, another connection she owed to Walter, for which she was paid rather less than the review copies fetched. But it also involved occasional expeditions to London for interviews with editors and other literary persons, and these were serious matters, as her diary showed: 2.3c Meet Jimmie at Achilles' statue. Fawn going-away dress, brown boa with brown chenille tassels, pansy toque, shot-silk parasol. brown gloves. fawn strap shoes. She did not always return from these expeditions the same day, which resulted in outbursts when Sandv 'clenched and unclenched his fists' and referred to his wife as 'my lady fly-by-night'." The impression one obtains on Sandy from reading the available literature is that he was sincere, hardworking, intellectual, a good husband but overall rather dull and relatively humourless. IV. Ivy Litvinov's Diversions. Perhaps following on from her mother's example; Lipman(p. 264): "Her one venture in the style of a fellow-travelling Agatha Christie aside [Her book "His Masters Voice"], most of Ivy's energies during the period of her husband's rise and subsequent downfall were employed in translating from the Russian, teaching Basic English in the face of the opposition of school administrators, raising her children in what she could manage of an English manner, and indulging a somewhat wayward sexuality. On this subject, Carswell, quoting Ivy, leaves little room for modesty or perhaps even for romance. In Berlin, she met a German doctor named Kurt, and felt: sort of happy. Had something I never had before. Beginning with an "o,"and now I feel serene, domestic and self-respecting.... [For a later tryst] Kurt arrived at 3. He came straight up to me and we simply fell upon each other with delight. He thought he had never seen me looking so nice and loved my hair. And 1 thought him ever so much more attractive.... [T]here is something clean and compact about him that is almost irresistible. We went together to Friedel's hotel at 6.30 and found her with her friend Beatus and to my dismay an "orgy" all fixed up for us 4.... 1 couldn't say anything as they all seemed to want it, but of course what I really wanted was Kurt all to myself. They all agreed that my hair was an enormous improvement and of course Friedel found it "a little perverse" so that was all right. We had a nice dinner and coffee together and I liked Beatus very much. A fat man, distinctly Regency, with an eye glass and soft white hands. Then we went up to Friedel's really huge room and all undressed and I may say tho' it was rather amusing at moments (especially the eyeglass of Beatus, to which he clung) I got no satisfaction out of the whole evening, tho' Kurt had me at least 4 times and at incredible length. He only had Friedel once and that made me frankly unhappy.... [And on another occasion she observes that] Beatus is infinitely more subtle and intelligent than Kurt.... He has not Kurt's marvellous potency and it is obvious that this could not be expected. You can't have everything. Besides he was not bad. ... What 1 specially like about Beatus is that he made me feel I was wonderful for him and said he could never forget me, while dear Kurt always makes me feel that it is he who is so wonderful. Of course Kurt would hardly have understood a dozen words of mine, our minds are so different...." V. Why didn't Alice Low (nee Baker) marry 'Frank' Hudleston? Ivy (p21) writes that the only present that John Hart (Sandy) brought his ladylove was "The Scottish Student's Songbook" Whereas (Mac - Frank Hudleston): "On Mac's evenings there was never any music, but he could be counted on to leave a long-necked bottle or a basket of fruit from Fortnum & Mason's on the hall stand before mounting the stairs to the drawing room. Gracie and Florrie told each other that there could be no comparison, which, of course, they meant any comparison was entirely in Mac's favor. That Wyn could hesitate for a moment was more than they could understand. "By their fruits ye shall know them!" cried Florrie, biting into the flushed cheek of a hothouse peach. "It isn't only that, it's the whole style - of the man," Gracie said reprovingly, digging into the skin of a tangerine with her thumbnail." Thus Sandy is depicted as being relatively mean but Mac's generosity is later put down merely to the fact that he had independent means. Ivy (p.23):"Sandy would rather die than keep a cab waiting twenty minutes," Florrie mumbled over the fat chocolate she had popped into her mouth the moment the hall door closed behind them. Gracie reminded her tartly that Mac did not have to live on his salary; he had a little money of his own. Florrie knew that very well; it was what was so nice about him. Further into the story Mac gives Winnie an engagement ring. Once Wyn is marked as Mac's 'property', even though Sandy is excluded for a while, this marks the start of a decline in the relationship. Ivy (p.27): Every evening was John Hedley's evening now, but Wyn did not behave in the least like a bride-to-be. She got up late, spent most of the day in her dressing gown, refused to hear a word about wedding clothes, and forbade her sisters to spread the news of the engagement. They noticed that she only put on the ring when her fiancé was expected. Florrie was distressed; Gracie did not like the look of things at all. By imperceptible degrees, the emotional barometer slipped from the high point in John Hedley's favor. Once he had gained his end, he turned out to be as selfish and inconsiderate as most men. Annie complained that he pushed past her without a word when she opened the door, whereas Mr. Hart always used to say, with a pleasant smile, "Good morning, Annie. Are the ladies at home?" Mr. Hart had greeted Gracie and Florrie with an old-fashioned chivalry which they remembered regretfully now that Mac's party manners had degenerated into the hollowest of jocular exclamations and an obvious impatience to get them out of the room and be alone with Wyn. Eileen was accustomed to her share in the courtship of her mother, but now if Wyn had her sent up to the drawing room in her gray frock and black sash, it was never long before Mac thrust a packet of butterscotch or a tangerine into her hand and told her to run away and share it with her little sister Doris. Once, having come unprovided, he insinuated a threepenny bit into Eileen's clenched fist, and led her to the door. "She doesn't know what it is," Wyn said fondly, but she felt vaguely affronted, and the next time Mac. came Gracie gave him back the coin. "Our children are brought up not to take money from visitors." The final turning point in Sandy's favour appears to be when Wyn tries to tell Mac about her third child who seems to be in hospital recovering from a leg operation. But Mac thought he knew everything already. Ivy (p.29):

"That same evening, Wyn told Mac she had heard from Sandy.

"She has two mites, hasn't she, Hart?" The question came from Scholes of Printed Books, a newcomer to the Museum (he had only been on the staff eight years and had not caught the tone of the establishment yet).

"What a good thing she chose Sandy!" Eileen said to Doris that night across the table between their beds. Doris couldn't have agreed more. What? A revolting old funny with dewlaps and a tasseled skullcap might have been their stepfather! Sandy was bad enough, goodness knew, but habit had overgrown antagonism, creating the tolerance a horse is said to feel for the bit. The girls slept like travelers who have reached haven after a narrow escape. At the end of the story Wyn thinks about the choice she had made. Ivy (p.36):"She could easily have married Mac, and she had deliberately chosen to marry Sandy. She had nothing to reproach herself with, and if it had been all to do over again, something told her that she would still have chosen Sandy. The thing now was to get a good night's sleep, and she closed her eyes resolutely. But the little cushioned hammock braced firmly under her chin irked her. She picked at the buckle, and when it stuck she tore the whole caboodle down over her face and flung it from her." The overall impression I get is that Wyn subconsciously realises that she should have married Mac. I think the fundamental reason she chose Sandy was probably because was felt she could be more in control of him than Mac. In section III above is stated that after marriage to Sandy: "she insisted on having what she called her 'personal life'"Wyn (Alice Herbert - nee Baker) became an excellent aunt/godmother to Frank Hudleston's daughter, Joan. VI. Bibliography Litvinov, Ivy. (1990) She knew she was right. Penguin Books - Virago Press. Lipman, Samuel. (1992) Music and More. Essays, 1975 - 1991 Northwestern University Press. Evanstown, Illinios. Carswell, John. (1983) The Exile: A life of Ivy Litvinov. Faber and Faber. London - Boston. No Author Stated.(1927) Miniatures from a French Horae dedicated to J.A. Herbert. Printed for the British Museum. |

|

|

|

|

|