'Sylvia Townsend Warner'

'Sylvia Townsend Warner'

|

|

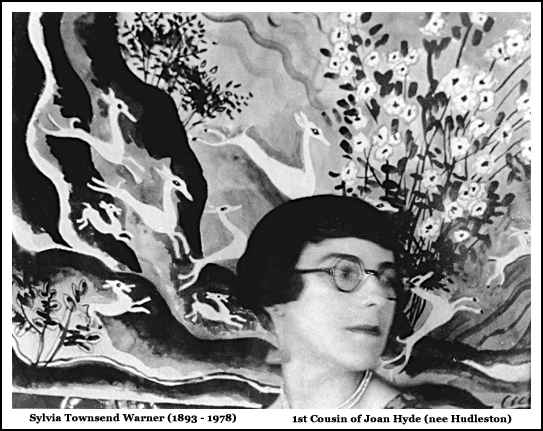

The following article from Joan's scrapbook is from the weekly John o'London and was published in 1953. Sylvia Townsend Warner "dislikes ink, the typewriter scarcely less". This study of her work and personality is by her namesake Oliver Warner who dedicated his new book on Captain Marryat to her. It is fitting to say that although Miss Sylvia Townsend Warner is my namesake and we have known one another for many years, we are not related. At the end of the twenties she and her black chow, William, and I and my young family shared for a time an early Victorian house in London; but the building has vanished, and as a solitary aunt, supposedly common to both of us - her name was Mary Esher - could never be spotted in the pedigree, our connections are quite intangible. Except for fleeting visits Sylvia has lived away from London since before the war, in Dorset, in Norfolk, on long visits to America and elsewhere, and now again in Dorset, where she shares a house, in a village not far from Dorchester with a friend of long standing. Few in this country are free of household ploys, but these have never been drudgery for Sylvia, who brings to the daily routine the same sort of volatile imagination which is to be found in her writing. Above all she likes cooking - and how well she cooks! In London days she gave memorable small parties. David Garnett was often her guest, as well as her publisher, Charles Prentice, both of whom were finished epicures. My mouth waters in recollection of what she provided, and I can recall to this day my shame when one day I put a bottle of Clos de Vougeot too near the fire. The wine hissed as it passed the neck of the bottle. "Ah mulled" said Garnett kindly, amid a laugh, and by good luck it was not ruined. In the deeper countryside, where the grind of living can be overwhelming in its handicaps and inconvenience, Sylvia has always made time to look about her, and to reflect on what she sees. She has a social conscience, and her mind works on at least two planes. There is one which sees the conditions of people as they are - too seldom pleasant; too often implying criticism of a structure of society, inherited or evolved. The other plane is that from which the greater part of her published work derives. And this .....(one word missing - David Hyde) has a timeless quality which all enduring poetry and fiction should possess, if what the wiser critics have laid down is to make sense. Before trying to indicate how Sylvia works, it may be well to say something of her background, and recall what she has written. She is the only child of George Townsend Warner, author of a notable short book on the writing of English, and known to generations of schoolboys for his share in a History of England which was one of the first successful attempts to make the whole subject come alive in the very teeth of the examiners. Her mother (Nora Townsend Warner - nee Hudleston - David Hyde) , among other skills, painted flowers with perception, and an aunt (Dorothie Purefoy Machen -nee Hudleston - David Hyde) - this time a very real and lovable one - married Arthur Machen.

From music, the transition to poetry is natural. The Espalier, her first collection of lyrics, appeared in 1925. It was followed by Time Importuned, by Opus 7 - a long satirical narrative - and by Whether a Dove or Seagull, which bears Valentine Ackland's name on the title-page along with her own. Her poetry has its distinctive flavour, but it is by her novels that she is best known. The earliest have something of the nature of fables. They have great economy, and their effect is as fragile and delicate as that of a jonquil. Lolly Willowes, 1926 was the first. It is a witch story, and it made her name overnight, though she has rarely been listed among the best-sellers. Then followed Mr Fortunes Maggot and The True Heart. Apart from stories, shorter and longer, which appeared in such collections as The Salutation, there was a break in her writing of fiction from 1929 to 1936, when Summer Will Show appeared. This was historical, a field she pursued in After The Death of John Juan and in her latest and most ambitious work, The Corner That Held Them. This book was published nearly five years ago, and has as its theme the story of a nunnery in a remote part of East Anglia in the earlier Middle Ages. It has something of the quality of a tapestry of its own period.

It is glib enough to say that her talk has a sparkle, but for once proof exists. If anyone should have the curiosity to explore just how she does talk, there is an actual dialogue with her, recorded many years ago in that early Victorian house, which appeared in Louise Morgan's Writers at Work (1931). Miss Morgan had among her other subjects in that little book such diverse people as W.B. Yeats, Sinclair Lewis, Edgar Wallace, Wyndham Lewis and Somerset Maugham, and I have never heard that Sylvia's talk suffered in comparison with theirs. The other side of Sylvia's art, her novels, give the effect, as indeed they should, of having been nurtured with great deliberation. They are seldom as simple as their story. For instance, although it would be easy to describe Lolly Willowes in terms of plot and although The Corner That Held Them could be summarized without undue strain, that would be to disregard their essential beauty. I cannot better illustrate what I mean than by saying that it is as if one were to describe the French masterpiece, the "The Lady with the Unicorn" as "a set of six early sixteenth-century representations in tapestry allegorising the senses, woven in the ateliers of the Loire, depicting the dress and furnishings of their time". This would be true enough in its way, but what actually makes that particular series so exquisite and moving are the same qualities which abound in Sylvia's novels; they have organised pattern rich glowing colour as well as graduation of tone; texture as well as surface. SYLVIA TOWNSEND WARNER writes slowly. She dislikes ink, the typewriter scarcely less, and as she never keeps note-books, all preliminary work is done in her head. For that reason, an idea for a book will germinate even longer than it takes to write, while revision, which with her is often radical, is apt to be the longest process of all. For her, as with many, writing is a compulsion. She allows nothing to interrupt the opening phases of a novel though at a later stage she is able to break off to write a short story and insists upon it. The "mood" of a novel is what first makes itself apparent to her. This may derive from a landscape, a turn of the head, a face in the crowd, even from a dream. For instance, it was a dream which gave the original impetus for Mr Fortunes Maggot, the tail end of a dream in which a man was standing by the edge of the sea, wringing his hands. Mr Fortune, it will be recalled, had his adventures on a desert island. Sylvia says that, in shaping her novels, she is less attentive to plot than to timing and balance - in other words she constructs as a musician composes. Poetry and the string quartet are, she considers, the two art forms most artists own, and if she herself still composed music, it would be in quartet form. At this moment she is working on a new novel. It will have English provincial life for background, and the period will be the earlier part of last century. I mentioned Middlemarch to her lately in conversation, and her eyes brightened in admiration; but it will not be like Middlemarch or indeed any other novel, for Sylvia is one of the most individual writers living, and when it appears, in two or three years time , it is as good in its way as The Corner That Held Them, it will be memorable indeed, and may bring with it the general recognition whose advent can never be foretold. Addendum - The birth of Sylvia:"The first thing to brighten the gloom of 1893 was the birth of Nora's first and only baby in December. Nora had called her Andrew before she was born, but she turned out to be Sylvia. George, my brother-in-law, sent us a wire, which arrived in Rickmansworth at breakfast time, and I ran wildly around the garden with joy. Aunt Annie was as delighted as anyone, but she thought of the two who would have so dearly loved their first grandchild, with the result that she broke down and wept while she was reading family prayers. But she cheered up when she went over to see little Sylvia; indeed we were all a good deal heartened. She was a dear good baby, fair and plump, and her parent's pride and joy was nice to see. Nora, in particular, could not take her eyes off her new daughter. By the way; Nora looked incredibly pretty, almost lovely. I was very proud at being an aunt when I was only fifteen. Altogether we felt better with the new interest in our lives; Frank was particularly delighted, for he adored babies. She, the baby, was an abnormally intelligent child, even at an early age. This is not surprising, when one considers that she was, later on, to write Lolly Willowes and the rest of her delightful books."

Note 1:

Note 2:

Sylvia Townsend Warner Society |

|

|

|

|

|